we're training AI on the wrong reality

Everyone's racing to build artificial general intelligence using Silicon Valley's data. They're training on the wrong universe.

Walk through Palo Alto and you'll see reality as AI understands it: orderly traffic flowing between clearly marked lanes, packages arriving exactly when promised, payments processing instantly without question. This is the training data teaching our most advanced models how the world works. GPT-4 learned physics from textbooks and human behavior from Reddit. Claude absorbed knowledge from Wikipedia and social dynamics from Twitter.

These models are brilliant at navigating a world that doesn't actually exist for most of humanity.

Meanwhile, in Lagos traffic, something extraordinary happens daily. Twenty million people navigate a city with no functional traffic lights, no reliable addresses, and no working credit system. They solve optimization problems that would crash any Western city. A danfo driver calculates thirty variables simultaneously—police checkpoint delays, fuel black market prices, passenger destination clusters, rain probability, alternate route congestion—making split-second decisions that keep the city moving. This isn't chaos. It's a different kind of order, invisible to systems trained on San Francisco's predictability.

The gap between AI's training reality and most human reality isn't a bug. It's the biggest arbitrage opportunity in technological history.

Consider what current AI can't do. It can't navigate a market where prices change three times during one conversation. It can't optimize logistics when roads exist or don't depending on rainfall. It can't predict customer behavior in economies where people use seven different payment methods for one transaction. These aren't edge cases—this is normal life for five billion people.

The standard response is to wait for infrastructure to catch up. Wait for Africa to become more like America so our AI can work there. This misses the point entirely. The chaos isn't a problem to be solved. It's the most valuable training data on Earth.

African systems aren't broken versions of Western systems. They're antifragile solutions to constraints Western systems never face. Mobile money in Kenya didn't copy American banking—it invented something better for reality as it actually exists. Okada delivery networks in Nigeria solve last-mile logistics using principles Amazon can't imagine. Informal credit circles in Ghana process trust calculations no FICO score captures.

This creates an extraordinary opportunity. While OpenAI and Anthropic perfect models for a narrow slice of orderly reality, whoever trains on Africa's complexity builds AI that works everywhere.

The technical implications are profound. Current large language models assume stable ontologies—that words mean the same thing across contexts, that causation flows predictably, that systems have clear boundaries. African reality breaks all these assumptions. Prices aren't numbers but negotiations. Addresses aren't locations but social networks. Time isn't linear but elastic, stretching and compressing based on relationships and requirements.

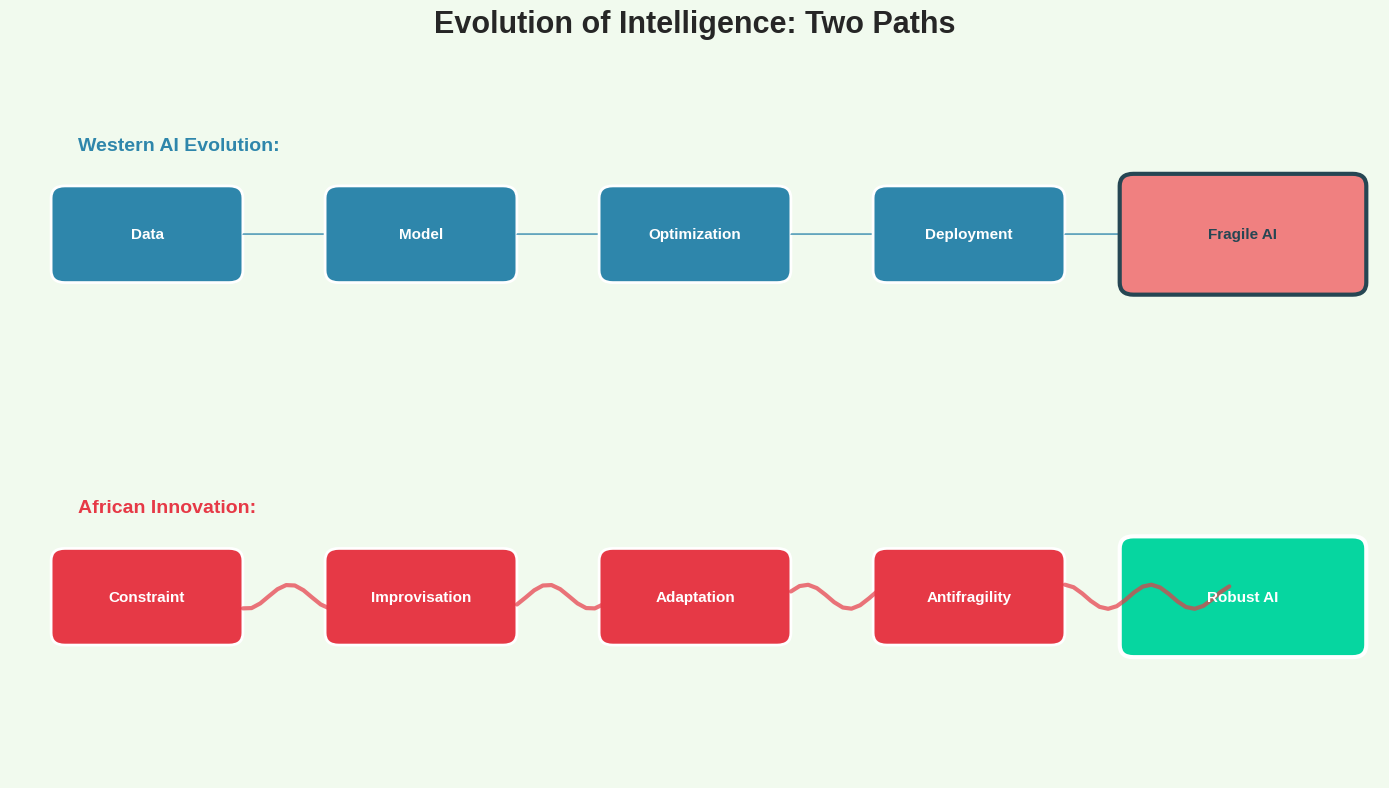

Training on this data would create fundamentally different models. Not just multilingual but multilogical. Not just robust but antifragile. Systems that thrive on uncertainty instead of breaking when reality doesn't match training data.

We already see hints of this possibility. Nigerian fintech startups routinely outperform Silicon Valley companies in fraud detection. Why? Their models train on adversarial data from day one. Every transaction is a potential scam, every user a possible ghost. The resulting systems handle edge cases that crash Western algorithms because in Lagos, every case is an edge case.

The same principle applies across domains. Healthcare AI trained on African diagnostic patterns—where doctors lack equipment but possess deep contextual knowledge—develops reasoning capabilities that pristine datasets can't provide. Agricultural models learning from farmers managing climate chaos surpass systems trained on Iowa's predictable seasons. Logistics algorithms optimizing for infrastructure that changes daily beat those assuming roads stay where you put them.

But the real revolution isn't in specific applications. It's in what intelligence means. Western AI pursues optimal solutions to well-defined problems. African reality demands satisficing solutions to poorly defined problems that change while you're solving them. One approach builds better calculators. The other builds actual intelligence.

This isn't technological romanticism. The data supports it. M-Pesa transformed financial inclusion by reaching 50 million users across seven countries with minimal traditional infrastructure—inventing mobile money before Silicon Valley knew it needed disrupting. Nigerian movie producers create globally competitive content at 0.1% of Hollywood budgets, generating the world's second-largest film industry by volume. Kenya's Silicon Savannah startups achieve 10x capital efficiency compared to Silicon Valley counterparts. These aren't accidents. They're what happens when intelligence evolves under extreme constraints.

The winners in AI won't be whoever builds the biggest models or secures the most compute. They'll be whoever trains on reality as it actually exists for most humans. That reality isn't in Silicon Valley's curated datasets. It's in the beautiful chaos of systems that work despite everything, solving problems the developed world doesn't know exist.

Right now, every AI company is making the same mistake the colonial powers made: assuming their version of reality is universal. They're building digital infrastructure for a world that's disappearing, training models on the past rather than the future.

Africa isn't waiting to develop proper infrastructure for AI. It's generating the training data for the only AI that matters: systems that work when nothing works, that thrive on chaos, that solve real problems for real people in the real world.

The question isn't whether Africa can catch up to AI. It's whether AI can catch up to Africa.