The Death of Resource Nationalism and the New Rules of Power

... The Day Sovereignty Died in Caracas

I was doom-scrolling at 2 a.m. Lagos time when the story broke.

Maduro. Extracted. Flown to New York. Sitting in federal custody by morning.

My first thought wasn’t political. It was structural. I sat there in the blue glow of my phone, ceiling fan humming overhead because “NEPA” had been generous that night, and I felt something shift in how I understood the world.

Not because of Maduro specifically. I don’t have a horse in that race. But because of what it revealed about the new rules.

A country with a flag. A seat at the UN. The world’s largest proven oil reserves. And none of it functioned as a shield when the moment came.

And if you’re reading this from anywhere in the Global South, this post is not really about Venezuela at all.

The Grammar of Receivership

Here’s what Trump said after the operation. I want to be careful here, because it’s easy to project onto these things, but his words were unusually clear:

“We’re going to run the country... We’re going to get the oil flowing. They should never have let Venezuela take back their oil.”

Set aside the politics for a second. Just look at the grammar of that statement.

“Run the country.” “Get the oil flowing.” “Let them take back their oil.”

This isn’t the language of regime change dressed up in humanitarian packaging. It’s the language of receivership. Of a company being taken over because management couldn’t deliver returns.

And that framing (resources as assets that need to be “flowing” to the right parties) tells you something about how power actually works now. Not through administration, but through chokepoints: sanctions, shipping access, insurance markets, spare parts, the ability to keep infrastructure online.

Venezuela had the oil. What it lacked was the operational capacity to turn that oil into leverage.

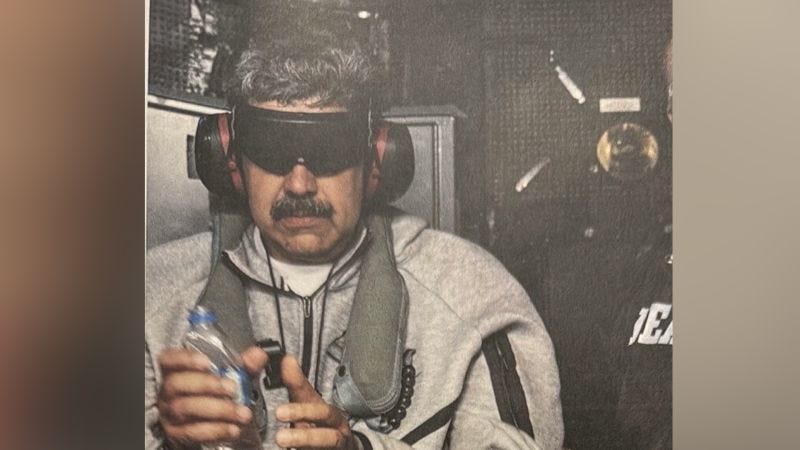

I keep coming back to this image: Maduro, presumably sleeping in the presidential residence one night, waking up in a New York detention facility the next morning. The world’s largest oil reserves didn’t slow that trajectory by a single hour.

The Silence of the Markets

Here’s the part that really gets me.

The day after “Absolute Resolve,” global oil markets... barely moved. Brent crude was trading around $60. WTI around $57. Down on the day, if you can believe it.

Down.

A sitting president extracted from the country with the largest oil reserves on Earth, and the markets shrugged.

Twenty years ago, this would have sent prices to $150. Every trading desk would have been screaming. The global economy would have braced for impact.

Instead? Analysts noted there was “ample global supply” and “limited immediate disruption potential.”

That’s the brutal math of it. Venezuela’s production had collapsed from 3.5 million barrels per day in the late 1990s to barely 900,000 by 2025. Years of infrastructure decay, capital flight, sanctions, mismanagement (pick your explanation) had hollowed out the capability to actually produce what the country nominally owned.

The reserves are still there. Hundreds of billions of barrels, sitting underground. But reserves are potential power. Production and export capacity are actual power. And actual power is what markets, and states, respond to.

Venezuela had become, in a real sense, all flag and no engine.

I think about this every time someone talks about Africa’s “resource wealth” as if it’s a trump card we can play whenever we need to. As if the cobalt and lithium and rare earths and oil and gas and solar potential and everything else automatically translates into leverage.

It doesn’t. It can’t. Not without the operational layer on top.

The Sovereignty Trap

I’ve started calling this the Sovereignty Trap, and I think it’s the central concept for understanding vulnerability in the 21st century:

Possessing strategic resources without the institutional and technological capacity to manage, defend, and monetize them makes you vulnerable. Not powerful.

Venezuela had the resource. What it lacked was capability. The capacity to extract, refine, export, maintain, and protect its own assets.

And here’s where I need to update my own thinking, because I used to believe resources were destiny. That having oil or minerals or agricultural land or whatever was the foundation upon which everything else got built. That you started with the resource and worked your way up.

But Venezuela flips that logic. The resource was always there. The capability decayed. And when capability decayed, the resource stopped functioning as protection.

It’s like having a castle with walls but no garrison. The walls are still there, technically. But they don’t actually defend anything.

The trap snaps shut when you realize this too late.

The Nuclear Dead End

I know what you’re thinking. You’re thinking: “Maduro didn’t need better refineries. He needed a nuke.”

And you’re right. If Venezuela had possessed a functional nuclear arsenal, the 82nd Airborne would have stayed in North Carolina. Nuclear weapons remain the ultimate “Do Not Touch” sign. That’s not a controversial observation. It’s just true.

But here’s the cold reality for Africa and the Global South: the nuclear door is closed.

The geopolitical cost of acquiring nuclear weapons today is total isolation. Look at North Korea. They have the bomb. They’re safe from invasion. But they’re also a hermit kingdom: economically strangled, dark at night when you see the satellite photos, and completely irrelevant to the global economy. Their “sovereignty” is the sovereignty of a prison cell. Safe from external threats, but unable to participate in anything that matters.

We don’t want to be North Korea. We want to be prosperous, connected, and sovereign. All three. And the nuclear path delivers, at best, one out of three.

There’s also the practical matter. Nuclear proliferation in 2026 means sanctions, isolation, potential preemptive strikes, and the permanent hostility of every major power. The NPT regime is fraying, but it’s not gone. Any African nation that pursued nuclear weapons would face consequences that would make the current development challenges look trivial.

So if we can’t build the Old Nuclear (and we can’t, and we shouldn’t), we need to build the New Nuclear.

What does that mean?

The Old Nuclear was a deterrent based on being too dangerous to touch. Mutually assured destruction. The logic of the gun.

The New Nuclear is a deterrent based on being too valuable to switch off. Too integrated into global systems. Too essential to the flow of energy, intelligence, and capability that everyone depends on.

It’s the difference between a country that can threaten to blow up the world and a country that, if you tried to destabilize it, would break supply chains and capabilities that you yourself need.

That’s the deterrent we can actually build. And it runs on energy infrastructure and AI capability, not uranium.

The New Oil is Silicon

Here’s where this gets uncomfortable for those of us watching from Africa.

Oil was the strategic resource of the 20th century. Whoever controlled oil shaped global politics, drew borders, decided which governments stood and which fell.

Compute is becoming the strategic resource of the 21st century. And the concentration is even more extreme.

The United States hosts approximately 75% of global AI GPU cluster performance. Seventy-five percent. China has most of the rest. Everyone else is rounding error.

Africa (18% of the world’s population) holds less than 1% of global data center capacity. The entire continent has less computational infrastructure than the Netherlands. Less than Belgium. Less than a medium-sized European country.

When people say “AI is the new nuclear,” they’re not being dramatic. They’re being precise.

Nuclear weapons created a binary world: nations that had them possessed ultimate strategic leverage; nations that didn’t faced permanent vulnerability. The technology was so complex, capital-intensive, and knowledge-dependent that only a handful of countries could develop it independently.

AI infrastructure is creating the same division. Training and deploying advanced systems at scale, reliably, on your own terms. This is becoming the threshold capability that separates sovereign nations from dependent ones.

And the U.S. government is explicit about this now. In a recent enforcement case, a federal prosecutor described advanced AI chips as “the building blocks of AI superiority” and “integral to modern military applications.”

Not “useful for business.” Not “important for innovation.” The building blocks of superiority.

The language tells you everything.

And so do the markets. Look at the world’s most valuable companies: Nvidia ($4.6 trillion), Apple ($4.0 trillion), Microsoft ($3.5 trillion), Alphabet ($3.8 trillion), Amazon ($2.24 trillion), Meta ($1.6 trillion). Seven of the ten largest companies on Earth are now AI-centric or major AI infrastructure providers. (I think the The "Top 10" list is now almost exclusively AI/Compute as Broadcom and TSMC have likely displaced traditional industrial giants even further).

In 2025 alone, AI companies raised $150 billion (in the US alone). That’s more than Africa’s entire annual foreign direct investment. The Stargate Project (a single AI infrastructure consortium) plans to deploy $500 billion over four years. That’s more than the combined GDP of Nigeria, South Africa, Egypt, and Kenya.

This isn’t a bubble. It’s not speculation. It’s the market recognizing where power actually lives now.

Redefining Sovereignty

So here’s where I’ve landed, and I’m genuinely uncertain whether this framing is too stark or not stark enough:

A country is sovereign to the degree that it controls its energy infrastructure and its AI/compute capability. Everything else is increasingly ceremonial.

I want to engage with the counterargument here, because it’s reasonable. You could say: “But most countries don’t have nuclear weapons and they manage fine. Won’t AI be similar? You can buy access, partner with providers, integrate into global systems without building everything yourself.”

Fair enough. And I think that’s true for some applications. If you need AI for optimizing logistics or running a chatbot, sure, you can rent that. Nobody’s going to cut off your access to customer service automation.

But that’s not where power lives. Power lives in the systems that run critical infrastructure. Power lives in the intelligence layer that makes military decisions, allocates resources, processes financial flows. Power lives in the capability to act on your own data without asking permission.

And increasingly, access to that power layer is being tiered and controlled. The CHIPS Act ($52.7 billion in subsidies, $200 billion in R&D funding) includes export controls that treat advanced semiconductors like nuclear material. These restrictions apply not just to chips, but to manufacturing equipment and technical knowledge. Not just to U.S. companies, but to foreign companies using U.S. technology anywhere in the world.

China responded by investing $150 billion in domestic semiconductor development. The EU launched a €43 billion Chips Act. Every major power recognizes what’s at stake.

When you’re in the inner tier, you get to build. When you’re in the outer tier, you get to subscribe. On terms that can change.

Venezuela had resources but couldn’t operate them. Much of the Global South has potential but can’t power it. The Sovereignty Trap has the same structure in both cases: nominally possessing what matters, functionally lacking what protects.

Why Energy Is the Bottleneck

There’s a cruel irony here that I can’t stop thinking about.

AI requires massive amounts of electricity. Global data centers consumed 415 terawatt-hours in 2024, and that’s expected to triple by 2035. The Stargate Project alone plans to deploy $500 billion in AI infrastructure over four years, and the energy requirements are staggering.

Meanwhile, Sub-Saharan Africa’s entire household electricity consumption is projected to reach only 430-500 terawatt-hours by 2030.

Let me make that concrete: the world’s AI infrastructure will soon consume more electricity annually than a billion Africans do for everything. Lights, cooking, refrigeration, all of it.

This isn’t an accident. Energy consumption correlates with GDP per capita at r=0.92. That’s not a loose association. That’s about as close as you get to a law in economics. There is no energy-poor developed country anywhere on Earth, and there never has been.

Nigeria has an installed generation capacity of about 12,500 MW. Actual generation? 4,000-5,000 MW on a good day. Less than 40% of what’s theoretically possible. And 40% of what does get generated never reaches a paying customer. Technical losses, commercial losses, theft, decay.

Nigeria’s per capita electricity consumption is about 150 kWh annually. South Korea: 8,000 kWh. The United States: 12,000 kWh.

Let that ratio sink in. Nigerians consume less than 2% of the electricity per person that Americans do. And we expect to compete in an AI-driven economy?

Here’s one more comparison that keeps me up at night: Nigeria’s entire federal budget is about $37 billion. Microsoft’s annual R&D spending is $33 billion. One American company spends almost as much on research as Africa’s largest economy spends on everything.

This is the foundation we’re building on. This is the grid that would need to power data centers, AI training clusters, the entire computational infrastructure of a modern economy.

I’m not saying this to be fatalistic. I’m saying it because any honest conversation about African technological sovereignty has to start here, with the electrons. You can’t run the future on generators and hope.

The Possibility Space

I don’t have a clean solution. I wish I did. But I can see a few possibilities emerging, and I’m genuinely uncertain which one we’re headed toward.

Possibility #1: The window closes and we miss it. The global AI infrastructure consolidates over the next decade, access tiers harden into something like the nuclear regime, and the Global South becomes a permanent consumer of intelligence produced elsewhere. We extract resources, export them, and import finished capabilities at prices set by others. A new form of the old dependency, but dressed up in API subscriptions instead of trade agreements.

Possibility #2: Some African countries manage to build genuine capability. Energy infrastructure, compute sovereignty, the operational platforms that turn resources into leverage. This requires patient capital, strategic policy, and a realistic assessment of what’s actually buildable in what timeframe. It’s harder than the first path but not impossible. South Korea did something similar with semiconductors. Estonia did it with digital government. India did it with digital public infrastructure.

Possibility #3: Something I’m not seeing yet. Maybe the AI capability curve bends in ways that make local capacity more accessible. Maybe new energy technologies change the economics. Maybe the geopolitics shifts in unexpected directions.

I’m betting on Possibility #2. Based on the conviction that Africans can create the infrastructure software that determines our own future. Not because I’m certain it’ll work, but because the alternative is waiting for permission that isn’t coming.

What Venezuela Teaches

I keep returning to that image: Maduro sleeping in Caracas, waking up in New York. The world’s largest oil reserves didn’t function as armor.

The lesson isn’t about military intervention or American power projection or any of the obvious geopolitical framings. The lesson is about what constitutes a hard shell in the 21st century.

Flags don’t protect you. Borders don’t protect you. Resources don’t protect you. Not by themselves.

What protects you is operational capability: the ability to run your own critical systems, extract your own resources, generate your own electricity, process your own data, make your own decisions without asking permission from infrastructure you don’t control.

Venezuela lacked that. Despite the oil. Despite the reserves. Despite the nominal sovereignty.

The question for Africa isn’t whether we’ll face a similar test. The question is whether we’ll have built the capability to pass it.

And the door doesn’t close with an announcement or a summit. It closes quietly, when the world finalizes who gets to produce intelligence and who can only consume it.

I’m writing this at 4 a.m. now. The fan is still spinning. “NEPA” is still holding. Outside my window, Lagos is doing what Lagos does: grinding forward despite everything.

The question is whether we’re grinding toward something, or just grinding.