Ship Fast, Think Slow

Why perfection is a bad system design choice

Hi everyone.

Yes, I know. It has been a minute.

Since the last post, quite a few of you have DMed, emailed, or casually thrown into conversation:

“Kay, did you abandon the blog or what”

First off, a massive thank you to everyone who has reached out, sent messages, and just generally checked in. I really appreciate it.

Short answer: no. The blog is alive. I haven’t posted in a while because I have been buried in a couple of things. One is some incredibly stubborn fonts that have been testing my patience. The other ... is that … I have been trying to write papers for scientific publications. (sighs!) Nobody told me it was hard, lol. I am still not yet published, and I am still at it, but trust that I am enjoying everything. And the process.

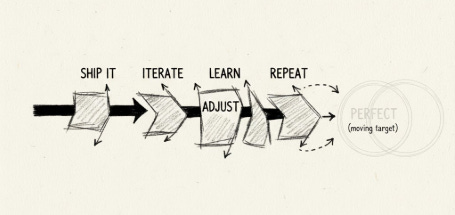

Speaking of process, I want to talk about something we have all heard a million times in tech and business: “Ship fast.”, “Move fast and break things.” “Fail fast, iterate faster.”

We all nod our heads and say, “Done is better than perfect.” But I want to explore why this is probably the most critical rule of all, using a little bit of systems thinking.

The real problem with “perfect”

We all know the line: there is no point trying to be perfect before you ship.

Sounds nice. Gets likes on Twitter. Inspires a Pinterest board. Then you open your laptop and spend three weeks adjusting a slide font size from 20 to 22.

So here is the big question is; why does shipping fast actually matter?

The answer isn’t about beating competitors to market or getting customer feedback earlier, though those help. The real reason shipping fast works has everything to do with how systems behave over time. And once you understand this, everything changes about how you think about timing, market entry, and why some mediocre products win while better ones die.

Let me explain using a concept from systems dynamics called path dependence.

The System Doesn’t Care If You’re Better

Markets don’t reliably select for the best product. They select for the product that gets locked in first.

Think of your new product, your startup, or your big idea. It’s a tiny ball balanced perfectly on the very top of a big, upside-down bowl.

That single point at the peak is the only place where everything is in perfect equilibrium. It’s also the most unstable place in the entire system.

Trying to build the “perfect” product in a garage, coding every feature, and polishing every pixel before you show it to a single user? That’s you, trying to keep that little ball perfectly balanced on that tiny point.

It is impossible.

The slightest breeze, a random event, a bug, or, more likely, a competitor, is going to knock that ball off the peak.

Shipping fast is about giving that ball a deliberate nudge down the side of the bowl you choose. The second that ball starts to roll, positive feedback kicks in.

In simple terms: The further it rolls, the faster it goes. It’s a “success to the successful” loop.

Your first 10 users love the product. They tell their friends. Now you have 20. That’s a reinforcing loop.

You get feedback from those first 10 users, you fix a major bug, and the product gets 5% better. Now it’s more attractive to the next 20 users. That’s another reinforcing loop.

A blog sees you have some users and decides to write about you, which gets you 100 more users. Loop.

This is exactly how VHS beat Betamax back in the day.

Betamax (from Sony) was first to market and, many will argue, was the superior technology. By all rights, Betamax should have won. But they were slow. They kept it proprietary. They were trying to keep the ball balanced perfectly.

The VHS team did the opposite. VHS had longer recording time and, critically, JVC licensed it to multiple manufacturers while Sony kept Betamax proprietary. They shipped fast and built partners. They got a small, early lead. That small nudge was all it took.

More manufacturers meant more units in stores. More units in stores meant more people bought VHS. Once VHS had a slightly larger installed base (more machines in homes), video rental stores started stocking more VHS tapes. Because stores had more VHS tapes, new customers bought more VHS players to access that content.

It was over for Betamax. The system “locked in” to VHS, not because it was “perfect,” but because it got a small, early lead and the positive feedback loops took over. Betamax was left perfectly balanced at the top of the hill, which, in a real market, means you have already lost.

Loop. Loop. Loop.

That’s a reinforcing feedback loop. Success breeds more success. The technical term is a positive feedback system, and once it starts running, it’s nearly impossible to stop.

The same thing happened with QWERTY keyboards. They are demonstrably worse than alternatives like the Dvorak layout, which was designed for speed and finger comfort. But QWERTY got there first. Typists learned QWERTY. Offices trained on QWERTY. The cost of retraining everyone became prohibitive. The system locked in to an inferior standard.

This is path dependence: small, early advantages compound into permanent dominance through reinforcing loops.

Why “ship fast” works: it shrinks your feedback loops

Perfectionism assumes the world is a static exam question. You think there is one correct answer. You think you can derive it from first principles. You think once you get it right, the problem will sit quietly and behave.

But reality is not a static exam. Reality is a system. And systems do not care how clever your first draft was. They care about feedback, timing, and how quickly you learn.

What you do today shapes the situation tomorrow, which shapes what you do next. You ship something. People react. That reaction changes what you build. That is where “ship fast” truly lives. Not in motivation. In feedback design.

When you ship fast, you’re not just launching a product. You are starting a race to establish reinforcing feedback loops before your competitors do.

Every customer you win early creates multiple advantages:

They spread word of mouth, bringing more customers (network effects)

They generate revenue that funds better features, attracting even more customers (spreading fixed costs)

They build habits and workflows around your product, making switching costly (installed base)

Their data helps you improve, widening your lead (learning curves)

Developers build integrations for your platform, making it stickier (complementary goods)

Each of these is its own positive feedback loop.

Here’s the critical part: these loops are time-dependent.

The earlier you activate them, the longer they have to compound. Ship six months later than your competitor, and you’re not six months behind. You’re fighting against six months of compounding advantages.

This is why Facebook beat Myspace even though Myspace had more users at one point. This is why AWS dominates cloud computing despite Google and Microsoft having superior technical capabilities. This is why M-Pesa transformed mobile money in East Africa while similar services failed elsewhere.

Timing wasn’t everything, but it was the spark that lit the fire.

Perfectionism comes from the belief: If I think long enough, I can avoid mistakes.

Systems thinking quietly says: No you cannot. The system is too complex. The only way to find out what works is to interact with reality.

When you ship fast, three important things happen:

1. You turn guesses into data

Before shipping, everything is theory. After shipping, it is binary reality.

Users did or did not use the feature. Investors did or did not like the model. Reviewers did or did not understand your argument.

That jump from theory to data is the whole game.

2. You shorten the delay in the loop

Long delays kill learning. If you take 6 months to create something, 2 months to gather reactions, 4 months to revise, you get one learning cycle a year.

Ship fast and the loop collapses into days or weeks. Same brain. Different outcomes.

3. You expose the real structure

You discover the truth, not your assumptions.

Users churned because onboarding sucked, not because of pricing. Your proposal failed because of governance risk, not IRR. Your paper is unclear because the introduction is confusing, not the equations.

Reality only reveals itself when the system talks back.

I have seen this with Energy Industry as well

This applies directly to energy systems. It explains why fossil fuels remain so dominant despite being worse for the climate and often more expensive than solar.

Fossil fuels won the feedback loop battle 100 years ago. That early advantage created:

Massive installed infrastructure (pipelines, refineries, gas stations)

A trained workforce with decades of expertise

Deeply embedded supply chains and logistics networks

Regulatory frameworks written around fossil systems

These aren’t just obstacles. They are active reinforcing loops that make fossil fuels harder to displace every single day.

For those of us deploying renewables in Africa, we aren’t just competing on price. We are competing against a 100-year-old system with deeply entrenched feedback loops. Shipping fast means you establish your reinforcing loops first. You train local technicians. You prove reliability. You build trust. Each of these activates feedback that compounds in your favor.

The Hidden Loop of Perfectionism

Here’s the nasty part. Not shipping also has a feedback loop.

It usually looks like this:

You delay shipping because “it’s not ready.”

While you delay, the idea grows in your head.

The bigger it feels, the more pressure you feel to make it great.

The more pressure you feel, the more you delay.

That is a reinforcing loop. The longer you wait, the scarier it becomes to start. This is why you have emails you never send. Figma projects that never see sunlight. Blogs waiting for the “perfect relaunch”. PhD chapters living on Post-it notes asking what they did wrong.

From the outside it looks like procrastination. From the inside it is a system optimised for fear.

The “stone in the jar” reality

There is a classic story:

You start with a jar containing one black stone and one white stone. You pick one randomly, then put it back along with another stone of the same colour. Over time the jar fills mostly with whichever colour got a small early edge.

Your creative life works the same way. Post one messy thread. It brings one unexpected client. That client brings another. Suddenly the side experiment becomes half your career.

Or delay for three years. Jar stays empty. You stay in your head.

Shipping fast is giving yourself more draws from the jar while the stakes are low.

But what about quality

Shipping fast doesn’t mean launching garbage and hoping it works. The loops only activate if your product works well enough for people to adopt it, use it, and recommend it. You need minimum viable quality.

But it does mean:

Launch with fewer features than you think you need, then iterate based on what users actually do

Accept that your v1.0 will embarrass you in two years, then ship it anyway

Focus on speed to the first 100 customers, not perfection for hypothetical millions

Build in public so you’re establishing credibility and relationships even before launch

Choose distribution channels that activate network effects early

“Ship fast” doesn’t mean “ship careless.” It means change what you’re optimizing for. Instead of optimizing the first version for quality, you optimize the system for learning speed.

This looks like:

Making Smaller bets. Write a 700-word blog before you attempt a 30-page paper. Build a scrappy internal tool before a full platform. Test a new pricing idea with one friendly customer before changing your whole website.

Having Explicit learning goals. Don’t just ask “is this good?” Ask: “What am I trying to learn from this version?” Will anyone sign up if we ask for a phone number? Does this explanation of capacity factor actually make sense to non-engineers? Can I write 500 words every week without dying.

Explore Cheap correction mechanisms. Design ways to recover quickly when you’re wrong. Feature flags instead of hard shipping. Pilot projects instead of continent-wide rollouts. Drafts with friends before journal submissions.

Quality still matters. It just moves to a different place in the system. You’re not trying to be perfect at version 1. You’re trying to be very good at version 10. The only way to get to version 10 is to actually ship versions 1 through 9.

Design your life like a learning system

If you take one thing from this, let it be this:

Design your work so that feedback arrives early, often and cheaply.

For anything you want to grow, ask these 3 systems thinking questions:

1. What is the stock - Skills, trust, revenue, published work.

2. What are the flows - Hours practiced, conversations, experiments, drafts.

3. Where are the feedback loops- Who reacts, how fast, how visible.

Then redesign your system with: Shorter cycles, Smaller experiments, More visible outcomes

“Ship fast” stops being hustle culture and becomes basic system hygiene.

Closing the loop

Your goal as a founder, a creator, or a leader is not to build the “perfect” thing. Perfection is a fantasy that keeps you balanced, vulnerable, and unstable.

Your goal is to start rolling.

The market is that inverted bowl, and the ball is going to fall. The only question is whether you’re the one who gives it the first push.

The world does not reward the person who thinks the longest in isolation. It rewards the person who learns the fastest from reality. And that starts with one uncomfortable decision:

Ship.

Even if it is messy. Even if it is small. Even if you are not ready. Especially when you are not ready.

Get it out there. Get that first user. Get that first piece of feedback.

Start the loop. And enjoy the process.

P.S. The ironic thing about writing this post on shipping fast is that I’ve been sitting on this draft for three weeks trying to make it perfect. Clearly I need to practice what I preach. If you are one of the people who nudged me to write again, thank you. You are part of the feedback system keeping this blog alive.

P.S. If you’re wondering whether I am using systems dynamics to rationalize my own impatience with lengthy development cycles, you’re not entirely wrong. But the math checks out, so I’m going with it.